The Endless Complexity of Knitting

One of the reasons knitting is so fascinating is because it can be so complex. The two basic stitches – knit and purl – can be manipulated in countless ways to create intricate textures, cables, ruching, and openwork lace patterns. Some evolved slowly as women varied traditional stitches handed down from previous generations. The variations in Japan developed differently from those in Britain. Americans are only now discovering them.

Mary Walker Phillips experimented in the 1960s to innovate other unusual stitches. She pushed the boundaries of the grid structure, creating the first real knitted art works.

If you’re not a knitter, here’s a little primer. Knitting is made of rows of looped stitches held on a needle. The knitter leads a loose end of yarn through the loops to grow the fabric. Passing the traveling yarn through each loop from the backside creates a knit stitch; passing it through the front side creates a purl stitch. The knit stitches look flat, while the purl stitches look like little bumps.

That’s the simple version. But, for hundreds of years, knitters have enlivened their knitting by twisting and crossing stitches over each other to create diagonal lines and cables. Or they may pass the traveling yarn through a stitch multiple times to create a bobble. Irish Aran sweaters are famous for both these techniques. Other knitters add loops of yarn between stitches to create openwork holes, and knit 2, 3, or more stitches together to bunch them into a wedge or point. Combining these two techniques creates lace patterns like those in Shetland knitting and Russian Orenburg shawls.

Unusual knitting from Japanese stitches

Sample page and leggings knitted from Knitted Socks East and West by Judy Sumner (HNA 2009) .

Restricted by the same structural limitations, Japanese knitters have manipulated stitches in ways different than those of Western knitters. One simple variation I have seen in Japanese knitting patterns is to intersperse cables with openwork in interrupting the lines. A more unusual technique found in Japanese knitting is to wrap the traveling yarn around large groups of stitches before knitting them, creating a belt around the stitches. Another stitch manipulation, which creates a more delicate horizontal bar, is to lift a stitch from the needle over two other stitches and let it drop. Japanese knitters also do a sort of embroidery-in-place on their knitting that creates a leaf or blossom shape on the surface of the knitting. This is done by dipping the needle down several rows and pulling the traveling yarn through from the back a couple of times before securing it with a decrease. These variations are undoubtedly the result of generations of creative experimentation, or capitalization on happy accidents, all within the confines of the knitted structure.

Sample page from Japanese Knitting Stitch Bible: 260 Exquisite Patterns by Hitomi Shida (Tuttle 2015).

The dean of modern knitting

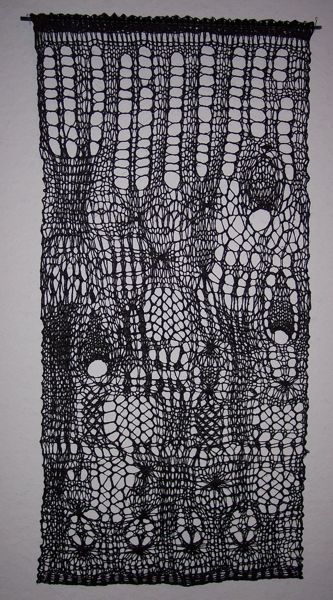

While knitting evolved in Europe and Japan over many generations, twentieth-century artist Mary Walker Phillips undertook purposeful experimentation with knitting while pursuing a master’s degree at Cranbrook Academy of Art in the 1960s. She invented new stitches, which she used in her architectural wall-hangings, inspired by the painter Paul Klee.

She made elongated stitches by wrapping the traveling yarn multiple times around the needle before pulling it through the loop. Phillips stuck her needle into stitches in the row below and pulled them into vertical lines that run from the top to bottom of her knitted panels. And she forced stitches to travel horizontally across the row looking more like weaving than knitting. She thoroughly explains all these stitches in her book Creative Knitting: A New Art Form, originally published in 1971.

Phillips has been heralded as the first person to introduce knitting as a form of artistic expression. Her abstract knitted hangings can be found in important museum collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago and the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York.

© 1965, Mary Walker Phillips, Knitted Wall Hanging.

Ripples of yarn

I knit the feathers on this waddling duck in a variation of the traditional Shetland pattern known as Feather and Fan. I found a soft wool yarn in the perfect combination of brown and grey – you’d think it was made for ducks! For the matt of grasses at the shoreline, I used Philips’ elongated fancy crossed throw and her three-into-three stitch pattern, knit in linen.